Mitochondrial dysfunction shows up in our cells well before blood tests can detect heart disease. These tiny power plants inside our cells produce more than 90% of the energy our hearts need to work properly[-1]. These mitochondria send out distress signals when they start to fail. These signals could reveal heart problems months or years before standard blood tests show anything wrong.

Scientists have known that faulty mitochondria play a role in heart disease for decades. Our understanding of how mitochondrial damage leads to clinical symptoms has grown significantly in recent years. Oxidative stress, genetic mutations, and metabolic disorders can trigger mitochondrial dysfunction. Doctors could spot these issues before permanent heart damage sets in. These early changes in mitochondria create a perfect opportunity to step in and take action.

This piece looks at the connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and heart disease. It explores why regular tests miss these early warning signs and how new technology might help catch these cellular red flags before heart damage becomes permanent. The text also gets into treatment approaches that target struggling mitochondria. These new methods could transform how we prevent heart disease.

How Mitochondria Power the Heart

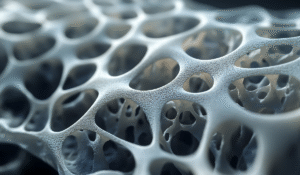

The human heart works non-stop throughout our lives and just needs an extraordinary energy supply. Cardiomyocytes contain the highest mitochondrial density of any tissue. These cellular powerhouses take up 30-40% of cell volume. The heart needs this concentration because cardiac mitochondria produce about 30kg of ATP daily—almost your entire body weight in energy currency.

ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation

Cardiac mitochondria create over 90% of the heart’s ATP through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This elegant energy conversion system sits on the inner mitochondrial membrane. The process starts when carbon-based fuels break down. Fatty acids provide 60-90% of cardiac ATP, while pyruvate, glucose, lactate, ketones, and amino acids make up the rest.

The OXPHOS machinery has five multi-protein complexes that work together. Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) lets electrons enter through NADH oxidation, and Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) offers another way in. These electrons flow to Complex III, which moves them from reduced coenzyme Q to cytochrome c. The experience continues to Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), where electrons reach their final destination—oxygen molecules.

As electrons move through this transport chain, protons pump from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space. This creates an electrochemical gradient, mostly as membrane potential. This gradient stores energy, similar to water behind a dam. Complex V (ATP synthase) then utilizes this potential. It lets protons flow back into the matrix and uses the released energy to turn ADP into ATP.

This system runs with amazing efficiency. The heart would use up its energy reserves in seconds without continuous ATP production. A mere 2 to 10 seconds without ATP would cause contractile failure.

Role of mitochondria in cardiomyocyte survival

Mitochondria do more than produce energy—they regulate cardiomyocyte survival. Calcium handling comes first among these functions. During cardiac excitation-contraction coupling, mitochondria buffer calcium through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU). This helps control cytosolic calcium transients and stimulates calcium-sensitive dehydrogenases inside the mitochondria.

Mitochondria stay healthy through dynamic processes of fusion and fission. Fusion lets mitochondria share their contents, including proteins and mitochondrial DNA. This effectively dilutes damage by mixing impaired organelles with healthy ones. Proteins like mitofusins (MFN1/2) on the outer membrane and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1) on the inner membrane coordinate this process.

Fission works differently. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) mainly controls it, helping to separate damaged mitochondrial components into daughter organelles. These can then be eliminated through mitophagy. This quality control becomes essential because cardiomyocytes rarely divide. They must maintain their existing mitochondria carefully throughout life.

Mitochondria’s strategic position within cardiomyocytes supports survival. They line up closely with sarcomeres and calcium release units. This creates an integrated network that connects energy production directly to contractile machinery. Mitofusin 2 strengthens this arrangement by tethering mitochondria to the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which helps calcium transfer between these organelles.

Compromised mitochondrial function severely affects cardiomyocyte survival. Damaged mitochondria create too many reactive oxygen species (ROS). These can harm mitochondrial DNA, membrane phospholipids, and electron transport chain complexes. On top of that, it can trigger cell death pathways when cytochrome c releases into the cytosol and activates caspases. Maintaining mitochondrial integrity isn’t just about energy—it’s crucial for cardiomyocyte survival.

What Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Heart

Reactive oxygen species are at the vanguard of cardiac mitochondrial damage. The heart’s enormous energy needs make it especially vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria take up only 30-40% of cardiomyocyte volume but generate nearly 90% of cardiac ATP. This makes their proper function vital for heart health. In spite of that, several mechanisms can disrupt these cellular powerhouses.

ROS generation at Complex I and III

The mitochondrial respiratory chain, mainly complexes I and III, produces most reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the heart. Complex I serves as the first entry point for electrons through NADH oxidation. Electron leakage happens mainly at the flavin mononucleotide site and creates superoxide (O₂⁻). This becomes a big problem during ischemia-reperfusion injuries. A deficiency of Complex I reduces respiration and speeds up heart failure.

Complex III moves electrons from reduced coenzyme Q to cytochrome c and also produces superoxide. As we age, Complex III activity drops in interfibrillar mitochondria. This leads to ischemia-reperfusion injury through combined defects in electron flow and increased oxidant production. About 0.2-2% of electrons leak from the electron transport chain and incorrectly transfer to oxygen, which forms superoxide.

ROS act as signaling molecules, but too much ROS production creates a destructive cycle. Superoxide damages electron transport complexes. This causes more respiratory chain dysfunction and triggers additional ROS generation. This explains why reoxygenation after hypoxia creates much more ROS while reducing oxygen consumption.

mtDNA mutations and impaired repair

Three critical factors make mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) highly vulnerable to oxidative damage. mtDNA has no protective histone proteins that shield nuclear DNA. It shows limited repair activity against damage. Its location near ROS production sites in the inner membrane increases oxidant exposure.

ROS damage to mtDNA shows up as single and double-strand breaks, base oxidation (like 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine), and point mutations. These mutations build up and disrupt electron transport chain function because mtDNA codes for 13 essential proteins in this system. The damage releases mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These activate innate immune responses that promote inflammation and atherosclerosis.

The damage runs deep—heart failure patients show more than 40% decrease in mtDNA content. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study tracked patients over the last several years. It revealed that lower mtDNA copy numbers link to higher heart failure risk. This mtDNA loss typically follows oxidative stress and reduces the expression of mtDNA-encoded genes and respiratory chain complex enzymes.

Calcium overload and MPTP opening

Calcium overload is another key mechanism behind mitochondrial dysfunction. Under normal conditions, calcium enters mitochondria through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) and exits via the sodium-calcium exchanger. Proper calcium handling plays a crucial role in mitochondrial function and cellular balance.

When stress causes mitochondrial calcium overload, it triggers a devastating event—the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens. This pore forms when either ATP synthase or adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) changes shape. It creates a high-conductance channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Once open, the mPTP lets molecules up to 1.5 kDa in size pass through and causes mitochondrial swelling.

Long-term mPTP opening has severe consequences. The outer mitochondrial membrane ruptures and leads to cell death through apoptosis and necrosis. Several factors affect pore opening. High levels of matrix calcium, inorganic phosphate, cyclophilin D, and oxidative stress activate it. However, molecules like adenine nucleotides block it.

These mechanisms join to create interconnected damage pathways. Too much ROS damages mtDNA and compromises energy production. At the same time, poor calcium handling triggers catastrophic membrane changes. These processes end up causing cardiomyocyte death and heart disease progression long before standard tests can detect problems.

Early Signs of Mitochondrial Damage Before Symptoms Appear

Mitochondria show subtle changes long before cardiovascular disease symptoms become visible. These molecular disturbances can signal cardiac complications months or even years before standard biomarkers appear. Scientists can potentially change disease outcomes by spotting these warning signs early, well before the heart shows any structural or functional damage.

Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential’s collapse stands out as one of the earliest signs of organelle distress. This potential creates a voltage difference across the inner mitochondrial membrane that powers ATP synthesis and keeps mitochondria healthy. Any compromise in this system points to serious dysfunction that comes before visible heart problems.

The molecular mechanisms show that lower mitochondrial membrane potential happens when the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens. This non-selective channel lets protons move freely across the inner membrane. The result is uncoupled oxidative phosphorylation and swollen mitochondria. The process works like an early warning system that alerts us to problems before clinical markers show up.

Several factors can set off this devastating chain of events. Calcium overload leads the list by making mPTP more likely to open. ROS buildup directly triggers the pore. The loss of adenine nucleotides removes key inhibitors that usually block pore formation. These factors meet to create perfect conditions for mitochondrial membrane depolarization.

Research has showed that mice with only one copy of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) are more sensitive to mPTP activation. These mice develop ROS-induced cardiomyocyte death despite looking normal at first. This finding highlights how cells can harbor problems even when everything looks fine on the outside—a significant concept for early detection.

Increased ROS and oxidative stress markers

Oxidative stress serves as another key early sign of mitochondrial damage. Heart tissue’s mitochondria produce most reactive oxygen species, mainly at respiratory chain complexes I and III. Under normal conditions, these ROS help control heart development, cardiomyocyte maturation, and calcium handling.

Higher ROS levels reliably indicate early mitochondrial problems. We see increased production of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrite, and hydroxyl radicals—molecules that damage cells. ROS damage also creates measurable byproducts like 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) from DNA oxidation, nitrotyrosine, and higher levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2).

This oxidative damage creates a destructive loop. ROS damages mitochondrial DNA that lacks protective histones. The resulting mutations then impair electron transport, which produces even more ROS. Scientists call this self-feeding process ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR), and it plays a key role in starting mitochondrial depolarization.

Altered mitochondrial dynamics in early-stage CVD

The third major category of early warning signs involves changes in mitochondrial shape and networking ability. Mitochondria constantly join (fusion) and split (fission) in a process called mitochondrial dynamics. Healthy cells need this balance, but it starts breaking down in early cardiovascular disease.

Healthy heart cells contain long, connected mitochondrial networks that efficiently distribute energy. Early disease states show too much fragmentation. This happens because cells make less fusion proteins like mitofusin 1/2 (MFN1/2) and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), while fission proteins like dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) become more active.

Oxidative stress makes mitochondrial fragmentation worse. Rising ROS levels block fusion protein production and promote fission. This creates another vicious cycle—more fission creates more mitochondria, which then generate more ROS and increase oxidative stress.

Clinical evidence supports these patterns. Diabetic patients’ skeletal muscles show more fragmented mitochondria than healthy people. High blood sugar leads to mitochondrial fragmentation in heart, liver, and pancreas tissue. Small, disorganized mitochondria appear in dilated cardiomyopathies and hibernating heart muscle before full heart failure develops.

Spotting these early signs—lost membrane potential, oxidative stress markers, and changed dynamics—gives doctors a chance to step in before permanent heart damage occurs. This could transform our approach to preventing cardiovascular disease.

How Dysfunctional Mitochondria Trigger Heart Disease

Damaged mitochondria become disease triggers instead of energy producers. They set off multiple harmful processes that end up damaging the heart’s function and survival.

Inflammation via mtDNA release and DAMPs

When damaged mitochondria release their DNA, it becomes a powerful trigger for inflammation. mtDNA is different from nuclear DNA because it keeps bacterial-like features, including unmethylated CpG motifs that strongly stimulate the immune system. mtDNA acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) once it gets into the cytoplasm or bloodstream. This activates several pattern recognition receptors.

The inflammatory response works through three main pathways. mtDNA activates Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) in cardiomyocytes and triggers NF-κB signaling. It also binds and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, which creates a protein complex that turns pro-interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and pro-IL-18 into their active forms. The cGAS-STING pathway spots mtDNA in the cytosol and activates interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which leads to type I interferon production.

This inflammation creates a harmful cycle. TNF-α and IL-1β directly hurt the heart’s ability to contract by reducing calcium-cycling genes like SERCA2. On top of that, these cytokines cause cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, which raises the risk of heart failure. We see this in clinical practice too – higher levels of inflammatory markers relate to worse heart failure and poor outcomes in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.

Apoptosis and necrosis in cardiomyocytes

The heart’s mitochondria arrange both controlled and uncontrolled cell death. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway starts when the mitochondrial outer membrane breaks down. This releases proteins that trigger cell death, including cytochrome c, which activates caspases. Stressors like hypoxia, oxidative stress, and too much calcium can start this process.

The heart can’t handle even small amounts of cell death. Research shows that just 0.023% of cells dying can lead to fatal dilated cardiomyopathy in mice within 8-24 weeks. People with heart failure have apoptotic rates between 0.08% and 0.25% – much higher than the 0.001-0.002% found in healthy people.

Necrosis is an even more destructive type of cell death. It happens when the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens, usually because of too much calcium in the matrix and oxidative stress. The open mPTP lets molecules move freely across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This destroys the membrane potential, stops ATP production, and makes mitochondria swell. When the outer membrane breaks, it releases both cell death triggers and DAMPs that keep inflammation going.

Energy starvation and contractile failure

The heart needs lots of energy, which makes it very sensitive to mitochondrial problems. Heart failure forces a move from fatty acid oxidation to glycolysis – a much less effective way to make ATP. Glycolysis provides less than 5% of what the heart needs, so this change leads to an energy shortage.

This energy shortage creates “mechano-energetic uncoupling” where the heart can’t make enough ATP to contract properly. Things get worse when acetyl-CoA builds up in cardiomyocytes. It changes mitochondrial enzymes like succinate dehydrogenase A, which reduces their ability to generate ATP.

Studies of human heart tissue back this up. Failing cardiomyocytes don’t contract well when they only have carbohydrates for fuel. Problems with calcium handling from damaged mitochondria also make it harder for the heart to relax, especially in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

These three problems – inflammation, cell death, and energy loss – work together. They turn the original mitochondrial damage into a progressive heart disease.

Why Mitochondrial Dysfunction May Outpace Blood Tests

Traditional blood tests detect heart problems only after major damage has happened. Meanwhile, mitochondrial dysfunction sends warning signals much earlier. This time gap between cellular distress and detectable blood markers gives us a missed chance to step in early and treat cardiovascular disease.

Delayed biomarker response in traditional tests

Standard cardiac biomarkers only show damage after heart tissue has taken a serious hit. These conventional tests come with their limits for early detection. To cite an instance, lactate measurements help identify mitochondrial disorders but can vary a lot, especially when samples are hard to get. Many patients with mitochondrial disease show completely normal blood lactate levels.

Other metabolites besides lactate might point to mitochondrial dysfunction, but they lack specificity. These traditional biomarkers help diagnose existing disease but miss the earliest signs of mitochondrial distress. Cellular damage needs to reach a certain level before it releases enough biomarkers into the bloodstream.

Real-time mitochondrial stress signals

Unlike delayed blood markers, mitochondrial dysfunction triggers immediate signals at the cellular level. Heart muscle cells can experience mitochondrial collapse during both lack of blood flow and when blood returns. This makes catching these early changes crucial.

Watching how mitochondrial function changes in individual heart cells of a living heart works better than conventional testing. This becomes especially important because restricted blood flow and its return lead to uneven changes in mitochondrial function across cells – changes that show up long before any symptoms.

The first mitochondrial stress signals include:

- Lower mitochondrial membrane potential

- Changes in mitochondrial fusion and splitting

- More reactive oxygen species

- Different calcium handling

Traditional biomarkers need cells to die or get damaged before showing up in blood tests. These mitochondrial signals, however, show active processes happening before permanent damage occurs. That’s why mitochondrial changes can show up weeks or months before standard blood tests catch anything.

Circulating mtDNA as an early indicator

Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA (ccf-mtDNA) stands out among new early warning signs. This genetic material leaks from injured mitochondria and shows up in blood before usual markers of heart damage appear. Heart attack patients’ mtDNA levels were 200 times higher than healthy people’s before treatment. After treatment, mtDNA levels dropped while troponin went up – showing that mtDNA appears before standard markers.

Research looking ahead shows that less mtDNA copy number by itself predicts more heart disease. One study found that when mtDNA copy number dropped by one standard deviation, the odds of coronary artery disease went up 1.29 times, heart attacks 1.43 times, and bypass surgery 1.58 times – even after considering age and sex.

This predictive power works for people of all backgrounds, making mtDNA a promising early warning sign. The link between ccf-mtDNA levels and blood sugar in heart disease patients with diabetes helps spot metabolism-related heart problems. Standard tests still matter for diagnosis, but mitochondrial signals – especially circulating mtDNA – could give us the early warning system we need to step in before permanent heart damage happens.

Emerging Mitochondrial Biomarkers for Heart Disease

Scientific advances now reveal sophisticated biomarkers that detect mitochondrial distress before standard tests show heart disease. These molecular signals give us early warnings about cardiovascular risks and help us understand disease mechanisms at the cellular level.

Plasma mtDNA levels and heteroplasmy

Mitochondrial DNA helps predict cardiovascular outcomes. Lower mtDNA copy numbers lead to higher cardiac risks—one study showed this is a big deal as it means that patients face greater cardiovascular disease risk. This relationship stays consistent in people of all backgrounds, which makes it useful as a universal biomarker.

The pattern of mtDNA heteroplasmy—multiple mtDNA variants within an individual—gives us an even clearer picture of cardiovascular risk. Heart tissue from donors with coronary artery disease (CAD) shows a 41.07% increase in heteroplasmic mtDNA variants compared to those without CAD. These variants affect non-synonymous residues that disrupt respiratory chain proteins. The total number of heteroplasmic single nucleotide variants rises by 48.76% in hearts from CAD donors versus non-CAD controls.

Heteroplasmy levels rise with age but increase faster in people with hypertension. Each person’s heteroplasmy pattern can vary between plasma and white blood cells, which shows that circulating mtDNA comes from many tissues. This gives us a full picture of whole-body mitochondrial health.

Mitochondrial ROS and lipid peroxidation products

Oxidative stress markers reliably show mitochondrial damage in cardiovascular disease. Lipid peroxidation products, mainly reactive aldehydes, leave measurable traces of mitochondrial oxidative damage. These include malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) from n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and 4-hydroxyhexenal (HHE) from n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

These markers prove valuable because of their stability and distribution properties. Aldehydes remain chemically stable and move easily through membranes, unlike short-lived reactive oxygen species. MDA, acrolein and HHE can travel far from where they form and act as signaling mediators.

Blood levels of these products relate to cardiovascular disease severity. Clinical studies link these oxidative stress markers to all major cardiovascular diseases, making them vital for risk assessment.

Mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs)

State-of-the-art biomarkers include mitochondrial-derived vesicles—small membrane-bound particles that bud from stressed mitochondria. These specialized structures, typically 50-150nm in diameter, transport damaged mitochondrial components to lysosomes for breakdown. MDV production increases faster (within minutes to hours) when exposed to mitochondrial stressors like antimycin-A and oxidative stress.

MDV cargo tells us a lot about cell health. When oxidative stress occurs, MDVs mainly carry proteins involved in redox processes, including those with oxidation-prone hyper-reactive cysteine residues. Without doubt, this selective enrichment shows which mitochondrial parts get damaged first as disease progresses.

Heart tissues produce MDVs normally but make many more during cardiac stress. Research shows that MDV formation happens more often than mitophagy in heart cells, which makes it better at detecting early mitochondrial distress. MDV levels first rise as a protective response, then drop as cells become too damaged to repair. This pattern relates inversely to heart cell death during oxygen deprivation.

By tracking these emerging biomarkers—plasma mtDNA heteroplasmy, lipid peroxidation products, and mitochondrial-derived vesicles—doctors may spot cardiovascular disease risks years before standard tests can detect problems.

Non-Invasive Tools to Detect Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Advanced imaging technologies give us a window into how mitochondria work and show dysfunction before symptoms appear. These non-invasive methods help us learn about cellular energy production without tissue sampling. Doctors can now detect heart disease earlier than ever before.

PET imaging of mitochondrial metabolism

PET stands out as the main molecular imaging technique that assesses mitochondrial function. It delivers high resolution and better sensitivity. Scientists use radiolabeled tracers that target specific parts of mitochondria and their processes.

18F-Flurpiridaz marks a major advance in cardiac PET imaging. This fluorine-18 labeled agent binds to mitochondrial Complex I and works specifically for myocardial perfusion imaging. Clinical trials show that 18F-flurpiridaz PET produces excellent images with good biodistribution and lasting cardiac uptake. The tracer showed better sensitivity and produced more high-quality images than SPECT in phase 2 trials.

18F-TPP+ (tetraphenylphosphonium) has proven useful to measure mitochondrial membrane potential—a crucial sign of dysfunction. Research confirms we can calculate tissue membrane potential (ΔΨT) in animals and humans with this method. Healthy volunteers’ average ΔΨT measured -160.7 ± 3.7 mV, which matches a mitochondrial membrane potential of -123 mV. These results align well with explanted heart measurements of -118 mV.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)

Phosphorus-31 MRS (31P-MRS) remains the only non-invasive way to assess heart’s energy state in living tissue. This technique detects phosphorus-containing metabolites and measures the phosphocreatine/ATP (PCr/ATP) ratio accurately. Heart failure patients typically have lower PCr/ATP ratios, which links to worse disease outcomes.

Carbon-13 MRS with hyperpolarization brings new capabilities to the table. The technique boosts 13C-MRS signals about 10,000 times and allows immediate metabolic flux measurements. Scientists most often use pyruvate, a three-carbon molecule, for these studies.

Oxygen-17 MRS presents a way to assess mitochondrial breathing in intact tissues. Scientists observe metabolic H217O production through 17O2 reduction. This method calculates the mitochondrial breathing rate directly instead of measuring its effects.

Circulating mitochondrial proteins and metabolites

Blood markers also tell us about mitochondrial function. Standard markers like lactate aren’t very sensitive because many patients with mitochondrial disease have normal blood lactate levels.

99mTc-MIBI washout rates show more promise and relate to mitochondrial dysfunction. Patients with congestive heart failure show higher washout rates than those without. The rate shows an inverse relationship with the heart’s ejection fraction, peak filling rate, and first-third ejection fraction.

These non-invasive tools give doctors a full picture of mitochondrial health. This knowledge helps start treatment before permanent heart damage occurs.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction

New therapeutic approaches target why mitochondrial dysfunction happens, showing promise in preventing heart disease progression before typical symptoms appear.

Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (MitoQ, SkQ1)

Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants mark a breakthrough in treating cardiac oxidative stress. MitoQ combines ubiquinone with triphenylphosphonium cation, which helps it gather in the mitochondrial matrix. This concentration inside mitochondria lets MitoQ reduce lipid peroxyl radicals and stop lipid peroxidation effectively.

MitoQ supplements improve vascular endothelial function and reduce aortic stiffness in adults with high baseline levels. SkQ1 (Visomitin), which is available for treating dry eye conditions in Russia, works by forming complexes with cardiolipin to prevent oxidative damage.

AMPK activators and SIRT1/3 modulators

AMPK works as the main sensor of low cellular energy status and activates catabolic pathways while stopping anabolic processes. AMPK promotes glucose uptake by moving GLUT4 to the sarcolemmal membrane when activated.

Resveratrol activates AMPK to protect heart cells by stopping hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis through blocking NADPH oxidase-derived ROS production. AMPK also activates PGC-1α through direct phosphorylation, which influences mitochondrial biogenesis.

Exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis

Exercise is the most available therapeutic approach to improve mitochondrial function. Training helps mitochondria tolerate decreased oxygen levels, which ended up improving respiratory function.

Regular exercise boosts SIRT1/3, AMPK, PGC-1α and NRF2—these proteins control mitochondrial biogenesis. Exercise preserves cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy models and prevents myocardial apoptosis by activating PGC-1α and Akt signaling.

Conclusion

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a central role in heart disease development and provides insights into cardiovascular health before standard tests can detect problems. These cellular powerhouses make up 40% of heart muscle cell volume. They alert us through decreased membrane potential, increased oxidative stress, and altered dynamics months or years before clinical symptoms appear.

A focus on mitochondrial health marks a radical alteration in cardiovascular medicine. Traditional biomarkers like troponin show up only after major damage occurs. Mitochondrial signals provide up-to-the-minute data analysis about cellular distress. Circulating mitochondrial DNA, heteroplasmy patterns, lipid peroxidation products, and mitochondrial-derived vesicles serve as early warning systems that could revolutionize preventive cardiology.

Advanced imaging technologies have improved our ability to detect mitochondrial dysfunction without invasive procedures. Doctors can now visualize mitochondrial metabolism directly in living heart tissue through PET imaging with specialized tracers like 18F-Flurpiridaz and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. These methods combined with circulating markers create detailed assessment tools to identify at-risk patients before permanent cardiac damage occurs.

The range of treatments has grown with mitochondria-targeted interventions. Antioxidants such as MitoQ and SkQ1 target oxidative damage within mitochondria. AMPK activators and sirtuin modulators boost mitochondrial quality control. Exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis remains a powerful way to improve organelle function and cardiac resilience.

Mitochondrial dysfunction changes our understanding of heart disease progression fundamentally. We now see cardiovascular disease not as a sudden event needing reactive treatment but as the result of cellular distress signals that start years earlier. This new view creates opportunities to prevent disease at its earliest stages—when mitochondria first send their microscopic distress signals, well before conventional tests detect issues.

Without doubt, future advances in detecting and targeting mitochondrial dysfunction will turn cardiovascular medicine from reactive to preventive care. The heart’s power plants might end up holding the key to predicting—and preventing—its failure.

Key Takeaways

Mitochondrial dysfunction in heart cells creates detectable warning signals months or years before traditional blood tests reveal cardiovascular problems, offering a revolutionary window for early intervention.

- Mitochondria send early distress signals – Decreased membrane potential, increased oxidative stress, and altered cellular dynamics appear long before conventional biomarkers like troponin show up in blood tests.

- Circulating mitochondrial DNA predicts heart disease – Plasma mtDNA levels and genetic variants can identify cardiovascular risk with 200-fold elevation in heart attack patients before standard markers appear.

- Advanced imaging reveals cellular dysfunction – PET scans and magnetic resonance spectroscopy now visualize mitochondrial metabolism in living hearts, detecting problems before symptoms emerge.

- Targeted therapies address root causes – Mitochondria-specific antioxidants like MitoQ, AMPK activators, and exercise-induced biogenesis can prevent heart disease by fixing cellular powerhouses directly.

- Prevention beats reaction – Understanding mitochondrial health transforms cardiovascular medicine from treating damage after it occurs to preventing disease at the cellular level when intervention is most effective.

This cellular-level approach represents a fundamental shift from reactive treatment to true prevention, potentially identifying and addressing heart disease years before it becomes clinically apparent through conventional testing methods.